A Few Thoughts on Musical Influence on the EGL Fashion Movement

Katherine RoseShare

Written by Lucy May

(Disclaimer: This is a mixture between a research article and an opinion piece, and therefore understandably may not be something all readers will 100% agree with)

In Western subcultural practice, there seems to be a consistent trend of having music, or some form of media, fuelling the spirit of the movement, as well as archetypal ideas of overall aesthetic within the movement. There is confusion or disconnect, therefore, between Western perceptions of subcultural activities in the East, that these must function in exactly the same way: that the fashion movement and spirit of EGL must have been born from the music. This is not necessarily completely true: this notion must be looked at from a variety of angles to understand music and musical performance’s relation to EGL fashion subculture as a whole.

The Hokoten Angle: (The Chicken vs Egg Duality)

It’s like the argument about whether the chicken or the egg came first, really. In Western perceptions of how EGL fashion came about, it started with the Harajuku hokoten. The hokoten in Harajuku existed from 1977 until the mid-1990s. These spaces were roads temporarily free from road traffic, where the public could gather to socialise, buy things, eat street food and enjoy impromptu concerts performed by start-up musicians and bands. Unlike the other hokoten spaces, the pedestrian paradise in Harajuku may have been the only one in Tokyo that was free of capitalist pressures and which actively encouraged freedom of expression. It is popularly believed by Western lolita enthusiasts that, following the closure of the hokoten-proper, the popular use of Jingu Bashi (the bridge passing between Harajuku station and Meiji Jingu) for subcultural socialisation was sparked by Visual Kei music fans (which we know to be the only j-fashion that is directly perceived by the West to have musical and musician idolisation as its raison-d’être).

EGL fashion is something that, these days, we adamantly claim has no association to cosplay. This is the truth: however, if the melting pot theory is to be believed, no matter how much the fashion is orphaned from cosplay, to say that it never had any relation would be a disservice to the fashion’s very evolution to what it is today. The fashion we came to know was, in part, worn as a creative, more femininely codified take on the outfits directly copied from or inspired by the stage costumes worn by the artists who may well have had humble beginnings in the very same hokoten.

On the other hand, oldschool EGL blogger Crypt_kasper1 described this phenomenon from a different angle, stating:

“The Harajuku bridge was a mecca for people in unique fashions and cosplayers (especially ones for visual kei) alike. It was the best spot to dress up in your best outfit, hang out with friends and wait for your picture to be taken. But above all, it was a place where Japanese youth could feel comfortable with their individuality and have a safe space to express their creativity through fashion. And with this platform, fashions and trends were not only able to evolve, but also mix with each other. Therefore, to say that there may have been an overlap between visual kei and Lolita because of their fans being so close to each other wouldn't be a far stretch. Don't forget about the Lolitas who were also visual kei fans too!”

There is a consensus here, then, that lolita fashion might have both developed from visual kei musical performance attire and aesthetic, and also been a thing completely separate from it. This brings us to…

Lifestyler Angle: The Secret Rebellion

Leaving home in ‘normal’ clothes so conformism-minded parents didn’t judge or forbid. Changing clothes upon arrival in Harajuku. Hanging out with like-minded friends. Getting photos taken in the street in the hope of being featured in a mook or zine. Going to a teaparty or to get crepes. Perhaps some, or all of the time, music was played in the background, part of the ritual and social practices, rather than the reason for them. We can see this naturalistic integration of music into lolita lifestyle consistently through the years. After the establishment of the ideals of the lifestyle lolita (which, incidentally, is different for each and every individual, both in the east and in the west), we can see how musicians used the ideas of that lifestyle and aesthetic to speak to (rather than market themselves towards) an exclusively lolita audience through their aesthetic and unique musical nuances. Lolita fashion, initially, was not a gimmick or technique of the capitalist music industry machine used to puppet musicians to cater to a particular audience.

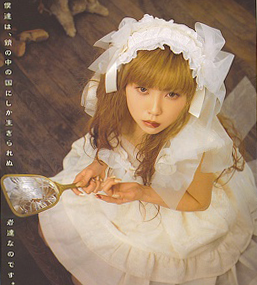

A key example of this is Moon Kana. Although she began her public career as a model for the Gothic and Lolita Bible (alongside being a singer), and her early music videos feature Moon Kana wearing lolita garments and engaging in either fanciful activities in nature, or lifestyler activities, there is a sense of naturalism and organic creativity that protects her from the capitalist machine and upholds her as ‘one of us’ in the rebellious cause. Her unique musical sound and vocal styling are both really rebellious in comparison to the silky-smooth male voices of Visual Kei artists and more traditionalist forms of Japanese popular music, her voice extreme and oftentimes described as unpalatable to those unused to her singing style. Moon Kana’s music stands firmly alongside the rebelliousness of oldschool lolita lifestyle in a way that is both raw and real, and also imaginary and fairy-tale-like. Perhaps no other artist quite captures the zeitgeist like Moon Kana.

There are other musicians that in some way capture the spirit of lifestyle lolita in the early days: a lifestyle that they themselves were active participants in. Kokusyoku Sumire and Nana Kitade (among others) performed concerts (of very rebellious music) alongside and during fashion shows at underground EGL events (as reported in early editions of the GLB): the integration of music part of the lifestyle (as still can be seen today by the fact second hand lolita shops quite often also stock second-hand C.D.s), but not as something more important in value than the fashion itself. Therefore, the rebellious spirit of the fashion itself (in the early days at least) was the most paramount part of fuelling the creative freedoms of the lifestyle. However, music, as well as art, décor and social practices, all fed in to a sense of rebellious self-empowerment divorced from the tiger-capitalism and pressures of traditional adult ideals rife in modern Japanese society. Creative individuals within the industry were, at the time, not fuelled by power, money and competitiveness, but rather a spirit of what the fashion meant to them and to those obtaining it to wear: a symbol of artistic self-expression and social freedom.

Over the years, there has been a radical change in how Japanese musicians utilise lolita fashion. Post-war Japan quickly undertook the concept of kawaii to soften their appearance and to employ it as a soft power towards potential political gain (or so it is perceived from a Western perspective). With the advent of the internet, and over the last 20 years, kawaii has taken over the world in a major way, and has infiltrated during that time into EGL lifestyle more than it ever was before. Perhaps this has to do with Misako Aoki being made a kawaii ambassador in 2009 after her many years of involvement as a model with Gothic and Lolita Bible, or the influences of musical artists like Kyary Pamyu Pamyu in the last 2000s/early 2010s capitalising to the pastel sweet style that was already being popularised within EGL by the late 2000s.

Kawaii, now involving lolita fashion, therefore became a super-power of national capitalism and international political viewpoint creator. That is the moment which oldschool lolita as we knew it became an even more rebellious way to wear the fashion. However you want to look at it, capitalism happened: and this is what has shaped Western perception of the way we think about music’s influence on EGL fashion! There is no other way to explain the disjoint between the past in EGL practices, and the way the fashion is now currently utilised, produced and disseminated (see previous post for a few further details).

And that, friends, is why we are ALL ABOUT the oldschool here at R.R. Memorandum! That lifestyle attitude of ‘If it makes you happy, do it!’ (cit. Momoko in Kamikaze Girls) is what we crave to have back within the fashion we hold so dearly!

1 http://marionettecemetery.blogspot.com/2016/01/lolita-conspiracy-theory-1-visual-kei.html